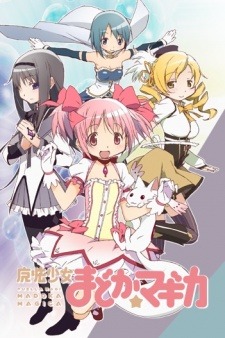

I just finished watching the first Puella Magi Madoka Magica movie, and, my goodness, was it emotionally shredding. It’s essentially 75% of the original series, more or less unchanged, all in one sitting. I watched the series about two years ago, and found it a soul-wrenching look at the darkness behind the magical girl trope. I have a lot of thoughts after watching all of this again at once, and I highly recommend watching it before reading further, as there may be spoilers, and it probably won’t make much sense otherwise.

Madoka is a show that is redolent with hyper-feminine images. The witches are flavored with girlhood: candies, crayons, roses, ponies and frills abound. Kyubei is the perfect kawaii mascot, with his cute voice, fluffy tail, and unblinking and perfectly round eyes. The magical girls themselves, though they use guns and swords, also let off sprays of ribbons and flowers as they fight. Femininity is to be expected from a magical girl show, though, and it is, indeed, one of the things I’ve always loved about the genre. Magical girls demonstrate that evil can be stopped and worlds can be saved even if you fight with rainbow sparkles and high heels. It’s a show of strength through nothing but feminine imagery, and what makes Madoka so dark, and so powerful, is how it turns all this on its head.

Girlishness is something that’s forced upon the Madoka and her peers from the start. The teacher in their school only seems to teach about the importance of marriage and how to properly cook an egg, and Kyubei presents his contract as a win-win: get one wish, and become the sparkling, mini-skirted heroine of your dreams. It’s a choice that anyone who’s grown up watching Sailor Moon or Cardcaptor Sakura would give their left lady-nut to do in a heartbeat. It is, of course, a sham, and the magical girls themselves either fight isolated and die alone, or have their dreams turned against them and become the evil that they fight. The promise of becoming a lovely heroine of justice is only a bill of goods that Kyubei sells them, because they believe that it’s what they want, as they’ve never been told otherwise. Girls by definition are children, and children are impressionable. They consume what they’re given, whether it’s coming from a teacher, a cute mascot, or marketing that sells tea, ponies and frills. That pre-packaged idea of girlhood is ultimately poison to the girls in this universe, and when Kyubei and others convince them that what they need is to mine that girlhood forever, it becomes their undoing.

Sayaka’s story in particular strikes a chord in me: she sacrifices her body and soul to save the body of the boy she loves, and then feels unworthy of him when she discovers that she unwittingly gave up her own body when she made that wish. She then chooses to do nothing but dedicate herself to saving people, only to judge people unworthy of saving when she hears some young men carelessly spouting misogyny in the subway. Sayaka’s wish was to heal- to take on the nurturing aspect usually afforded to women- and became disconnected from herself and humanity as a result, with no other road left but to destroy herself and become a witch- the definitively feminine evil of the show.

One of the only exceptions in this whole world is Madoka’s mother. She’s a high-powered businesswoman married to a stay-at-home dad, which is already an inversion of a common trope. She’s not an absent (read: fridged) mother, or an antagonistic one, as is common in this genre of television. She’s affectionate toward her daughter and takes an interest in her life. When Madoka comes to her for advice, what she says is unusual; Madoka doesn’t have to be a heroine. She tells her daughter that it’s ok to mess up, it’s ok to not always be strong, and sometimes acting cowardly is the best thing you can do in a situation. Madoka’s mom warns her that sometimes friends in trouble just cannot be saved, even if your intentions are pure and your will is strong. This advice is the most realistic message thus far in the story, and far more mature than the overly-simplistic fairy tale fed to her by Kyubei, and by extension, other magical girl shows.

There are two more movies left to go, with my re-watching of Homura’s Groundhog Day heartbreak backstory, and then whatever new fate lies beyond that I will soon discover. I’d love to hear anyone’s thoughts on what I wrote, but no spoilers, please!

ReplyDeleteI'm gone to tell my little brother, that he should also visit this website on regular basis to obtain updated from latest information. craigslist seattle